Homework... long has it been the bane of many a teacher's working life - that annoying extra little bit of workload that so often feels like an add-on; something to do because we feel we should be doing it but perhaps not 100% sure why. And then when we set it... oh the battles it can create with those students who just don't get it done! It's understandable when some of us in the profession question the point of setting it at all!

However, this is probably going a bit too far. Instinctively we know there is a benefit to homework (there is), maybe what we need is just some convincing of what the benefit is, as well getting a better idea of what makes homework meaningful. Let's see what the research tells us.

|

| At it's worse homework can be a barrier to learning. |

Homework can make a significant difference to student outcomes

In 2015 research was conducted into the effectiveness of homework as a strategy to to improve performance in maths and science [Fernandez-Alonso et al. 2015]. In short it found homework made a positive difference to outcomes. Below are some further thought provoking findings:

- Students who were set regular homework performed better compared to those who only received it occasionally.

- Frequency of homework was more important than the amount of time spent on an individual piece of homework.

- Students who completed there homework by themselves achieved on average 10% better than those who got help from their parents.

- More time spent on homework did not necessarily mean better outcomes.

|

| If students can't do the homework by themselves progress won't happen. |

What makes homework effective?

Dylan William famously stated that 'most homework set is crap'. In Fernandez-Alonso' et al's, study they also acknowledge that a lot of homework set was inefficient and lacking in impact (i.e. overblown and too time consuming). Therefore, if we want the best outcomes from homework we need to consider what makes homework effective and efficient. Based upon Fernadez-Alonso's findings and other research by Vatterott we should think about the following questions when we plan and set homework:

- What is the purpose? If it has none, don't set it.

- Is it a good use of the time it requires to complete? If it's not, re-think it.

- Is it something that students perceive as meaningful? If they don't know its meaning, have we told them?

- Is it achievable - can students complete the homework without adult support? If they can't how can we blame them when they don't do it?

If the homework you plan has a positive answer to these questions then most likely it will be a motivational task that will have an impact and completion rates will increase.

| Carefully considering why we set homework is the clear solution to making it meaningful. |

The R&D group - A word from Ash Choudhury and Anna Walczynska

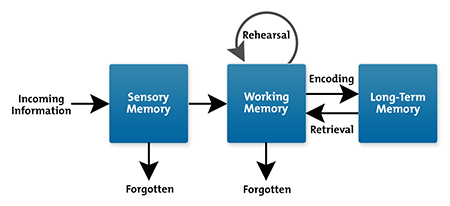

In our first meeting we discussed the current state of homework practice across the school and acknowledged that whilst there were lots of great strategies taking place there were plenty of areas where things were not ideal. One of the main discussion points was what the main purpose of homework is - Is it about supporting memory and recall, rehearsing skills learnt in lesson, or a means to encouraging independent learning or research?

As a group we considered memory and recall to be the primary purpose, after all, knowledge should be at the core, although independent learning would be a positive side effect of the implementation of any homework strategy. Following our sharing of a range of memory recall strategies practitioners decided to draw on five that they felt could be useful models to base a sequence of homework tasks upon:

As a group we considered memory and recall to be the primary purpose, after all, knowledge should be at the core, although independent learning would be a positive side effect of the implementation of any homework strategy. Following our sharing of a range of memory recall strategies practitioners decided to draw on five that they felt could be useful models to base a sequence of homework tasks upon:

- Over-learning

- Spaced Repetition

- Retrieval practice

- Acquisition before application

- Interleaving

- Graphic/knowledge organizers

We will soon be planning and implementing some new homework strategies with these discussions in mind and look forward to letting you know what we find out.

If Denbigh staff have any questions feel free to speak to any member of the R&D group.

Ash and Anna

@ash_achoudhury

@AnnaWalczynska

If Denbigh staff have any questions feel free to speak to any member of the R&D group.

Ash and Anna

@ash_achoudhury

@AnnaWalczynska

Useful links:

- https://blog.innerdrive.co.uk/how-helpful-is-homework

- https://researchschool.org.uk/huntington/blog/homework-what-does-the-evidence-say

- https://blog.teamsatchel.com/what-makes-a-good-piece-of-homework

- https://time.com/4466390/homework-debate-research/

- https://content.ncetm.org.uk/itt/sec/KeelePGCEMaths2006/Research/Homework%20Research/ReportSusanHallam.pdf

- http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept10/vol68/num01/Five-Hallmarks-of-Good-Homework.aspx

- https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/edu-0000032.pdf