| An evidence informed practice (EIP) model. |

At Denbigh we have tried to encourage a more evidence informed approach by trying to support staff in an outward focus toward the research evidence. However, there have been problems in doing this. Firstly, trying to filter through all of the burgeoning research is not an easy task. Finding credible research is often a confusing and time consuming job that teachers struggle to make the time for. Thankfully, there are some great filters out there; from the large organisations like the Chartered College of Teaching or ResearchED to the growing numbers of bloggers who are engaging with the research and trying to make it meaningful to the classroom teacher. Twitter probably remains the easiest way for individual teachers to engage in discussions on the the latest research evidence. Also, in many schools like Denbigh, leaders are trying to act as filters themselves by presenting some the best evidence informed practice to teachers directly.

|

| Organisations like ResearchED are useful to teachers as they to a lot of the filter a lot of the best research. |

Nevertheless there is still a problem. Unfortunately education is not an empirical science - it is a social one. We are dealing with human beings (both students and teachers) who are complex, subjective and individual. Any given evidence informed strategy, by itself, could be affected by so many other variables that knowing for sure it is the strategy that is making the difference is difficult. The reasons why a strategy may work or fail could just be down to doing something different (a kind of placebo affect) or maybe it works or fails because of the way it is implemented. Replicating a successful strategy from one school to another is also not a simple copy and paste job as school contexts are vastly different. Therefore relying on research based strategies from beyond our school is not going to be enough.

This is the reason why that, just because a strategy may have evidence to support its efficacy in another school or in academia, it doesn't mean it is going to work for us straight away, if at all, in our context. That is why we need to employ our own professional expertise and judgement and our understanding of our own unique contexts to any new strategy. We need to see what works for ourselves by engaging in our own research.

|

| Studying human behaviour including learning is a difficult task - we are very complicated animals. |

So at Denbigh this is what we are trying to do. Firstly we have introduced all staff to one area of research focus (we have done some filtering). Secondly, we have tried to give some time for all staff to understand, discuss and reflect upon that research and the potential strategies that they imply in teaching and learning. Now, as we go into the spring term, if we have not already begun to do so, we intend to implement these new strategies in our teaching to test whether they make an impact. Now how do we do this research?

Firstly lets remember we are not engaging in academic research, we are engaging in small-scale action research. It's not meant to be that complicated. Below is a simple step by step guide on how to do it.

- Intent - Define the aim - What are you trying to achieve?

- In our research groups we may have discussed our ideas and aims. An example: "I am aiming to improve the long term memory retention of year 10 GCSE RE students knowledge of Christian beliefs with a particular focus on middle ability year 10 boys who have last year underachieved in comparison to other gorps." Notice it is clear and measurable and links to a specific set of knowledge.

- Implementation - The strategy - How are you going to do it?

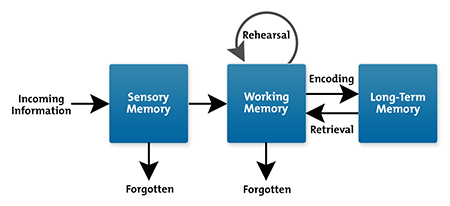

- This is where we think about how we can bring about the aim. This should relate to the research and related strategies we have discussed in our research groups. My example: "I plan to achieve my aim by implementing a method of dual coding in my Google slide presentations and exercise books based upon the principles of cognitive load theory as well as plan regular low stakes retrieval practice tasks in lessons." Notice that this is not overly complex - when I come to write it up/present it I will elaborate and give more detail.

- Impact - The evidence - How will you know it is successful?

- Firstly you will take a sample of a group you are looking to assess the impact in. I could look at the entirety of year 10, a class or a small sub group within a class... it depends what our aim is. You will also need to collect some evidence to show an impact. Much of this evidence will occur naturally, such as assessment data, exercise books/steps to success data etc. Some data you may actively collect such as a student questionnaire or simple student interview which could take place informally during a lesson. Whatever you decide to collect it shoud not be a laborious process, the simpler the better. Take the following example: "I will be implementing the strategy with all my year 10 classes however I will focus on my middle ability boys who in RE have been underachieving at GCSE in comparison to other groups. I will interview a small sample before the strategy is implemented and then at the end - asking them questions of their long term memory and their perceptions of the strategy. I will also look at their performance in retrieval practice tests and the end of unit assessments over the spring term and compare them to previous test scores." From this data I should be able to determine whether the strategy has had a positive impact or not and make some conclusions.

During the spring term most of us, if we have not already started, will be implementing new strategies and begin collecting some data. By Easter and the early part of the summer term we certainly should be able to notice whether these strategies have made an impact and hopefully share some of the best ideas with all of us at our summer professional development day and through the Denbigh teaching and learning journal and blog.

|

| The Adam Boxer session and the importance of the knowledge rich curriculum has inspired many new strategies in my own teaching this year - hopefully they have inspired some new ideas for you too. |

What are the benefits of this process?

It is important to remember is in itself based on evidence as a way to improve teaching and learning and outcomes. In short here are three benefits:

It is important to remember is in itself based on evidence as a way to improve teaching and learning and outcomes. In short here are three benefits:

- We will become better teachers. By taking part in reflective practice such as this we will become a staff body that is constantly looking for ways to improve and get better. Engaging in research will help us become more informed of the best teaching and learning strategies and by conducting research we will be able to select the best ideas that work for us and implement them into our routine practice.

- We will create better learners. Many of the new strategies we implement will make a demonstrable positive difference to student outcomes. Whether they make huge differences or marginal gains it will be worth it.

- We become better leaders. By sharing our practice we will all become better leaders. Whether you are an NQT or a member of the senior leadership team, by engaging in research and sharing the outcomes we will begin to influence and lead other members of staff across the school and beyond. This generates a culture of leadership that everyone can be a part of.

Good luck engaging in your research in 2020. We as a senior leadership team are looking forward to hearing all the great new innovations that we will be happening soon.

Ian Stonnell